Healthcare Terminology Systems Explained (part 3)

In this third article in our series, we will focus more on common clinical terminology components. While not all clinical terminologies contain all of these common components in their native formats, most have them represented in some auxiliary format.

Clinical terminologies include core building blocks such as concepts, terms, relationships, value sets, and mappings. Together, these components provide the structure needed to accurately represent, query, and exchange healthcare data across use cases.

(For a deeper dive, read part one Clinical Terminologies and Why They Matter, part two How Clinical Terminologies are Released, and part four What Makes Healthcare Data So Difficult?)

Note: As you read this article, if you're interested in browsing healthcare terminologies, exploring how they're stored in a FHIR Terminology Server, or learning more about TermHub, visit us at https://www.terminologyhub.com.

Concepts and Terms

Many of the clinical terminologies we have discussed in the previous articles are concept oriented.

According to Merriam-Webster Dictionary a concept is:

Something conceived in the mind

An abstract or generic idea generalized from particular instances

For a human to really understand a concept, we need some way to describe it using words. A term is a single word or phrase that has an exact meaning in some uses. We can assign multiple terms or synonyms to represent a given concept so that different people can understand that concept based on the context or domain in which they are using that conceptual idea.

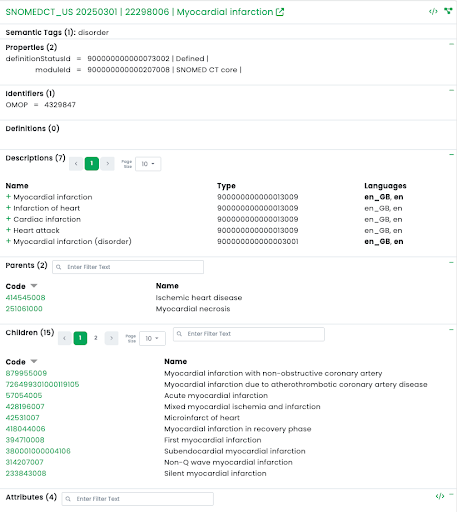

For example, the term “myocardial infarction” is preferred when describing the concept in medical settings, but most patients are going to be more familiar with the term “heart attack” when they are describing this concept. We can take this a step further and even translate terms into other languages allowing this concept to be used worldwide.

Myocardial infarction SNOMED CT concept with English and Spanish terms

Among standard terminologies, there is a great deal of variability about how to name what we are calling a “term” in the previous paragraph. Words like term, name, description, synonym, atom, label, rubric, and others are all commonly used to refer to this thing. Suffice it to say, even terminology has a terminology problem. Regardless of the word we use, each conceptual idea requires one or more things to name it in one or more languages so that it can be effectively referenced.

In addition to having a sequence of characters associated with a particular language, terms often also have a “term type” which describes the intended purpose of the term and how it should be used in a particular context. These term types are used to define what the preferred or display term is for a concept compared to what is a synonym that can be used for searching or assisting in natural language processing.

Parent — Child Hierarchy

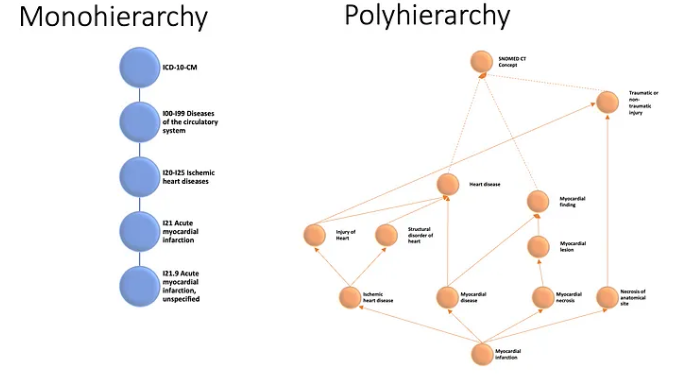

ICD-10-CM Monohierarchy vs SNOMED CT Polyhierarchy (partial representation)

While humans can use a concept’s terms to understand the meaning of a specific concept, there is more we can do to further define a concept that will make it more understandable by both humans and computers. By grouping a concept together with like concepts, we can assign a parent concept(s) which can provide further context for the meaning of a concept.

For example, we can group the concept “myocardial infarction” together with other heart diseases and therefore both humans and computers can understand that “myocardial infarction” is a type of “heart disease”. Clinical Terminologies like SNOMED CT allow you to assign multiple parents (called a polyhierarchy). For example, “myocardial infarction” has four parents at this article’s publication time, as seen in the image above.

Relationships between other Concepts

SNOMED CT Relationships and Inverse Relationships

In addition to these parent-child hierarchical relationships, some clinical terminologies specify other relationships between concepts that can provide concepts with a logical definition.

When we think of a particular instance of a disease, there are some things that are not always true about that disease for all instances. If we think about COVID-19, the range of possible symptoms versus the ones any particular individual experiences can be quite different. Therefore, a concept would be linked to the other concepts that are necessary and sufficient to define it (like it is an infection caused by the SARS-COV-2 virus). These kinds of relationships also go by a variety of different names, including defining relationships, roles, and object properties.

Some clinical terminologies also include weaker associations that link meanings to other ones in ways that are not part of a strict logical definition (meaning they are not necessarily always true). These kinds of relationships provide navigational and informational connections, like drugs that are indicated to treat specific conditions.

Value Sets / Reference Sets

Now that we have concepts, terms, and relationships, we need some way of identifying which concepts are needed for a particular purpose.

One way of grouping the concepts needed for a particular purpose is by defining what is called a value set (or sometimes referred to as a subset, or reference set). These are lists of concepts developed by Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) or made available through National Release Centers (NRCs). Some examples of these sources would be:

HL7 Value Sets that are used in a variety of HL7 published artifacts can be found at https://terminology.hl7.org/valuesets.html. These value sets define administrative and supporting concepts needed to implement standards like FHIR and C-CDA.

US Value Set Authority Center (VSAC) contains value sets from a variety of sources which can be searched, viewed, and downloaded. https://vsac.nlm.nih.gov/

NRC Reference Sets — Many of the National Release Centers distribute Reference Sets and Value Sets via their terminology distribution sites. As some of the content they distribute may require a license to use within their country they typically require a log in to access. For example: United Kingdom TRUD, Canada Infoway, United States National Library of Medicine (NLM).

In addition to standard/national value sets, organizations may develop their own local value sets depending on internal needs and use cases. When developing value sets locally, it is recommended to start with one of the standard/national value sets, and add or remove concepts from there.

Value sets associated with the “Bone structure of distal humerus”

Mapping

In our previous article, we talked briefly about the need to integrate disparate clinical terminologies where there is clear overlap and a need to have them work together. This involves recognizing equivalency between concepts from the two different clinical terminologies and creating a link between the two codes. A good example of this type of collaborative integration work would be the recent announcement from SNOMED International and Regenstrief Institute. You can find out more information about that agreement here.

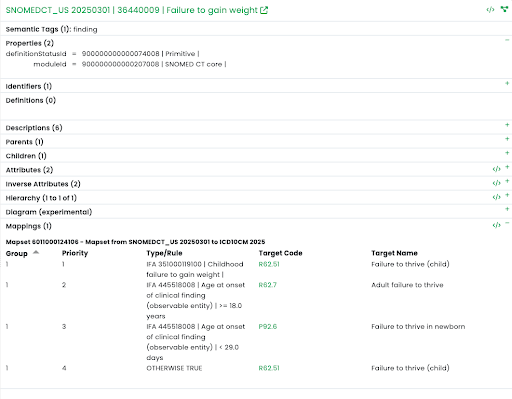

Mapping is something different. With mapping, a common goal is to have one-to-one exact mappings, but in a lot of cases that is not possible. Not all clinical terminologies represent concepts at the same level of granularity or in some cases will combine meanings into a single code. For example, the ICD-10-CM code I21.9 Acute myocardial infarction, unspecified maps from multiple SNOMED CT concepts (22298006: Myocardial infarction, 57054005: Acute myocardial infarction, etc.).

A very typical use case involves mapping a local code set or formal clinical terminology (like SNOMED CT) to a classification or reimbursement system like ICD10 or CPT.

Standard Mappings (Standard clinical terminology to Standard clinical terminology)

There are several mappings that have been produced by Standards Organizations like SNOMED International, National Library of Medicine (NLM), and Regenstrief Institute. These mappings are typically developed for a specific national (or international) use case. Some examples are:

SNOMED CT to ICD-10-CM

SNOMED CT to ICD-O

LOINC to CPT

SNOMED CT “Failure to gain weight” concept mapped to ICD10CM

Local Mappings (Local terminologies to standards)

Many legacy systems have some form of local codes. In many cases, these local codes were built using billing or drug codes that were not meant to capture data at the level needed to support semantic interoperability, assertional knowledge (i.e., clinical decision support rules), or procedural knowledge (i.e., treatment protocols).

While moving forward, these legacy systems can be converted to natively used standard clinical terminologies that would support these goals, there is still all the data that has been previously recorded using these old legacy terminologies. This data will need to be mapped to make it useful going forward. These mappings can sometimes be difficult because standard code targets are not always available at the appropriate level of detail.

Automated Mapping

In a perfect world, there would be pairwise mappings between every possible pair of clinical terminologies that share concepts in the same concept domain. This would allow automatic translation from any coding system to any other coding system by simple lookup in a table.

Part of the reason this does not exist is that terminologies are constantly being updated on different schedules and the maintenance requirements of keeping all such pairwise maps up to date for each combination would be extremely onerous. Another reason is that mappings between terminologies are often use case-specific, such as generation of billing codes from clinical data.

An alternative approach is to use generalized automated mapping approaches that take content in one form (say ICD-10-CM codes) and programmatically produce codes needed in another form (say SNOMED CT codes).

While automated mapping approaches can be used to programmatically map a term to a clinical terminology when the matching algorithm reaches a certain minimum confidence threshold, this approach is best used to seed map projects with candidates. From there, expert human reviewers can curate and maintain those maps to provide high-quality, use-case specific connections between terminologies.

At West Coast Informatics, we have worked on mapping use cases such as public health reporting, medical coding, linking national drug databases, and linking consumer entered healthcare statements to conditions and procedures. You can learn more about these projects athttps://www.westcoastinformatics.com/mapping-solutions

Explore how these concepts work in practice with our TermHub FHIR Terminology Server, a cloud-based platform for browsing, querying, and managing clinical terminologies. Thanks for following along with the Healthcare Terminology Systems Explained series. The final article will be published next week — be sure to follow us on LinkedIn